Occasionally, I publish a post from a guest blogger and today is no exception. My brother kindly sent me the following post which confirms that blogs have no boundaries. Enjoy!

In the 18th and 19th centuries, there existed a very real fear of being buried alive. The worry was stoked by disturbing newspaper reports, including one that appeared in the New York Times. The brief described a young man by the name of Jenkins who had been buried the day after his supposed death. Apparently, when the coffin was opened many days later by his relatives, who wished to move the body to the family burial ground, they were greeted by a ghastly sight. Jenkins’ body was lying face down, with much of his hair pulled out. Scratches lined the inside of the coffin, as if Jenkins had tried to claw open the lid.

Across the Atlantic, in 1895, physician J.C. Ouseley lent a measure of plausibility to the frightful accounts. After conducting extensive research, he claimed that as many as 2,700 people were buried prematurely in England and Wales annually. Though Ouseley’s statistics were likely exaggerated, groups like the London Association for the Prevention of Premature Burial (LAPPB) were founded to curb the chances of such a nightmare scenario actually occurring. With wide public support, the LAPPB and other smaller organizations lobbied for burial reforms and demanded that doctors thoroughly inspect fresh corpses for signs of life.

As a result of the public outcry, many physicians developed and instituted quite a bizarre arsenal of diagnostic procedures for verifying death. Preventing mistaken burial became a top priority, as well as a marketing gimmick. Bereaved relatives would pay higher prices if it ensured that their loved ones weren’t confined to coffin while still alive.

In 2002, medical historian Jan Bondeson researched some of these quirky methods for his spooky, fascinating book Buried Alive. Science writer Mary Roach neatly and humorously summarized them in Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers.

“The techniques,” Roach wrote, “seemed to fall into two categories: those that purported to rouse the unconscious patient with unspeakable pain, and those that threw in a measure of humiliation.”

The soles of the feet were sliced with razors, and needles jammed beneath toenails. Ears were assaulted with bugle fanfares and “hideous Shrieks and excessive Noises.” One French clergyman recommended thrusting a red-hot poker up what Bondeson genteelly refers to as “the rear passage.”

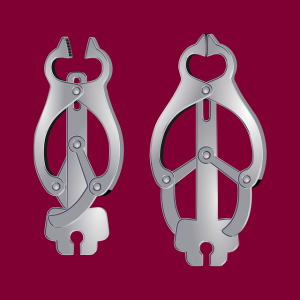

A French physician invented a set of nipple pincers specifically for the purpose of reanimation.

Another invented a bagpipelike contraption for administering tobacco enemas, which he demonstrated enthusiastically on cadavers in the morgues of Paris. The seventeenth-century anatomist Jacob Winslow entreated his colleagues to pour boiling Spanish wax on patient’s foreheads and warm urine into their mouths. One Swedish tract on the matter suggested that a crawling insect be put into the corpse’s ear. For simplicity and originality though, nothing quite matches the thrusting of “a sharp pencil” up the presumed cadaver’s nose.

None of these methods gained wide acceptance, however, especially because there existed a far simpler, much less humiliating, albeit smellier method of determining death: putrefaction. After two to three days of the body being left out, optimally in a hot, humid environment (or not so optimally if one is prone to queasiness), it becomes rather apparent if the person is alive or dead. The abdomen will start to swell and grow discolored, and there will be a stench.

Oh, will there ever be a stench.

But, if the stench isn’t obvious enough, you can always wait five days, at which point the skin will start to blister.

Nowadays, of course, we have more refined and scientifically valid methods of determining death. Doctors can precisely monitor heart rate, breathing, as well as brain activity. When such signs are absent, a person has probably passed on. They also watch for hypostasis, where the blood pools in the lower portion of the body, and algor mortis, a rapid drop in body temperature.

At its most basic, death is end of life. There’s a caveat, however, because scientists still can’t entirely agree on how to define life. So for now, death remains at least partially shrouded in mystery. But rest (in peace) assured, our powers of observation have grown advanced enough that you almost certainly don’t have to worry about waking up inside a coffin.